With this newsletter and the new academic term CSAD enters its second year. There is much to report on. The strengths and orientation of the Centre's work are now well defined. Electronic projects are central to our activities. In the last newsletter, Dorothy Thompson wrote that she had seen the future and that, for documentary studies, at least a part of that future seems to be digital. In this Newsletter we have further evidence in support of this proposition, with reports on the digitisation of the Vindolanda tablets and on a symposium at the Centre in which the digital future for documentary studies-its limits as well as its advantages-was specifically addressed. Digital technologies can help us to see more clearly at the margins of our studies and to share our resources and communicate our results more widely and efficiently. They enable, but do not replace scholarship.

The week of 23 to 27 September was a busy one for the Centre, the British Museum's Department of Prehistoric and Romano-British Antiquities and Dr. David Cooper of Oxford University's Celtic Manuscripts Project. Taking advantage of a week's pause in work on the digitisation of manuscripts in the Bodleian Library's collection, Dr. Cooper drove the project's Kontron camera down the motorway to Bloomsbury where it was to be used to begin an intensive and ambitious project to digitise the ink writing-tablets from the Roman fort of Vindolanda, near Hadrian's Wall (see Newsletter No.2, p.3). Preliminary experiments had already taken place in Oxford, using a writing-tablet of an identical type from Carlisle, made available by Dr. Roger Tomlin. A format and a calibration (715 nm in the infra-red spectrum) for the camera had earlier been established in London using the British Library's Kontron camera under the expert guidance of Tony Parker and Dave French.

When work began on Monday morning, a production line was rapidly established: a team of three BM staff removed the tablets from their protective mounts and reassembled them with captions and scales for photography. Images were taken at a standard resolution of 480 dpi which allowed even the largest tablets to be captured within a single frame and the same setting to be reused with only minor adjustments from one tablet to the next. Each captured image was then cropped down and saved to disk while the next tablet was being prepared. By the end of the week, the routine and repetitiveness of the work had left everyone rather dazed, but the results justified our exhaustion. The whole of the unpublished trove of writing-tablets from the excavations of the 1990s had been captured on disk, together with a sample of the earlier material from the 1980s, published by A.K. Bowman and J.D. Thomas in 1993. It took five people, working from 10 till 5 each day for a week to complete over 500 scans. Eventually, we hope to scan all of the tablets discovered between 1974 and 1994.

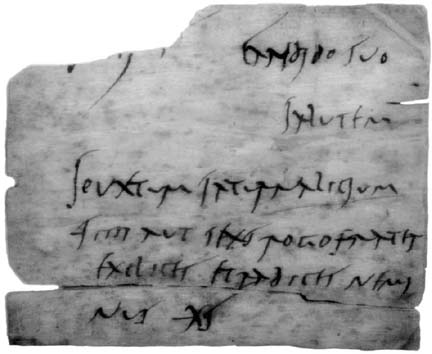

Tab. Vindol. II 301 (letter from Severus to Candidus), photographed with Kontron camera (© British Museum 1996).

We were also able to add scans of a dozen stilus tablets, photographed under variable raking light for the Centre's joint project with the Department of Engineering Science (Prof. J.M. Brady and Li Fu-Xing) on the image-enhancement of incised texts.

The digitised images of the new and unpublished ink tablets of the 1990s will be used by Dr. Bowman and Prof. Thomas in the editing work currently under way. They complement the brilliant infra-red photographs already taken at Vindolanda by Alison Rutherford and are the more vital because development plans at the BM threaten to make the originals less accessible over the next few years. Preliminary comparison of the new and the old images shows the relative strengths of conventional and digital photography. The strong contrasts and clear lines yielded by the former are hard to match, but the ability of the digitised images to be viewed across a range of contrast settings with variable magnification on a computer monitor offers important advantages for the process of decipherment-in particular, in distinguishing between ink and other extraneous marks.

Digital images have a vital role to play in the future of documentary studies. Not the least of their advantages is the accessibility they offer for material such as the finds from Vindolanda. We now have the possibility to create files consisting of images of the original tablets and scans of the infra-red photographs, along with transcriptions of the texts, commentaries and other scholarly apparatus. Such developments fit very well into wider current strategies for the electronic dissemination of scholarly material (e.g., through the Arts and Humanities Data Service).

We are very grateful to Dr. Cooper, Tony Parker and Dave French and to

Dr. T.W. Potter and his staff at the British Museum for their investment

of time, expertise and enthusiasm in this project.

On Friday 31 May and Saturday 1 June, a small group of scholars involved in a wide variety of imaging projects concerned with ancient and medieval documents met at the Centre to review shared interests. The participants were:

Prof. R.S. Bagnall (Columbia University and Christ Church), Dr. A.K. Bowman (Christ Church, Oxford), Prof. J.M.Brady (Dept.of Engineering Science, Oxford University), Mr. L.D. Burnard (OUCS), Dr. Rosalie Cook (Macquarie University, NSW), Dr. D.G. Cooper (Libraries Automation Services, Oxford University), Dr. C.V. Crowther (CSAD, Oxford University), Prof. Marilyn Deegan (IIELR, De Montfort University), Prof. T. Gagos (University of Michigan and British Academy Visiting Fellow, CSAD), Dr. R. Kilpatrick (King's College, London), Dr. G. Lock (Institute of Archaeology, Oxford University), Dr. D. Obbink (Christ Church, Oxford), Mr. A. Prescott (British Library), Dr. P. Robinson (IIELR, De Montfort University), Dr. S. Ross (The British Academy), Mr. H. Short (King's College, London), Dr. R.S.O. Tomlin (Wolfson College, Oxford), Dr. H. Walda (King's College, London)

Papers were presented on the following topics:

Imaging Greek papyri: the APIS Project. (Roger Bagnall, Traianos Gagos)

Imaging carbonised papyri. (Dirk Obbink)

Imaging Medieval documents. (Andrew Prescott, David Cooper, Peter Robinson)

The Daedalus Project. (Harold Short, Hafed Walda, Robin Kilpatrick)

Imaging inscriptions. (Charles Crowther)

Wooden stilus tablets and lead curse tablets. (Alan Bowman, Mike Brady, Roger Tomlin.)

Round Table discussion. Chair: Marilyn Deegan

*

Marilyn Deegan of the International Institute for Electronic Library Research reports below on the discussions:

The idea of this workshop grew out of the interests of the two institutional bases which organised it: the Centre for the Study of Ancient Documents (CSAD) at Oxford University which is using and pioneering digital techniques for the study of ancient documents, and the International Institute for Electronic Library Research (IIELR) at De Montfort University which is carrying out research into the technologies and intellectual foundations necessary for the development and delivery of the digital library to scholars and students. It was felt that a meeting which transcended discipline boundaries would be an excellent way of keeping abreast of developments across a broad range of technological and intellectual concerns. We were interested not just in the representation of text electronically, but in a number of projects which had as their aims the creation, display, and enhancement of images of text and artefacts written on or carved from a wide variety of materials: ink on paper, parchment, or papyrus; inscribed materials on stone or the secondary images of these impressed on paper-so-called squeezes-incisions on wax, wood, or lead, stone sculpture; and the digital representation of what are already secondary images: photographs and microfilm.

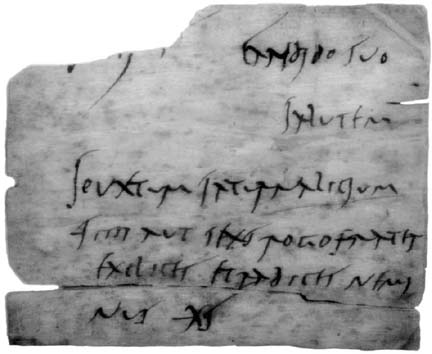

Example of a digital image of a manuscript captured with a Kontron camera from the Celtic Manuscripts Project: Oxford, Bodl. Lib., MS Rawl. B. 506, fol. 2r (detail), reproduced by permission of the Bodleian Library.

The materials under discussion dated from the seventh century BC to the nineteenth century AD, and many had suffered varying degrees of damage or wear throughout their long history, having been burnt, carbonised, scraped, torn, cut, folded, excised, worn, discoloured, damaged by water or chemicals, and sometimes even affected by the attempts of past scholars and librarians to read them using processes which have lost for us forever some of the vital information encoded on the artefacts.

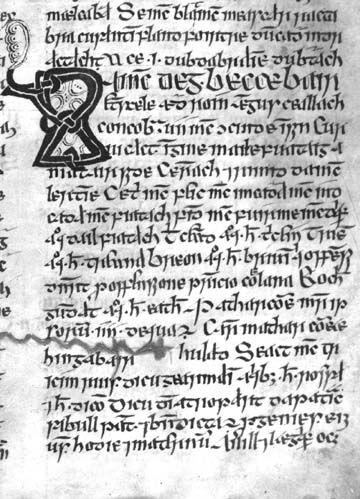

Roman lead tablet. This example, a surface find from near Peterborough in Lincolnshire, is to be published by Dr. R.S.O. Tomlin in Z.P.E. 114 (1996).

The papers presented at the symposium discussed most of the above kinds of materials and the practical problems involved in handling the objects and the different methods of rendering these into some kind of digital representation. A key question asked was, having produced a digital form of the document, do we then know more than we knew before? Can digitisation enhance readings and find us new information? In some cases it seems that it can: the Beowulf Project at the British Library, for instance, has revealed readings in the manuscript of the poem which have been inaccessible in the past. But this, though important, was not felt to be the only, or even the main reason for digitising these materials. The enhancement of scholarly access to widely dispersed materials which can be brought together virtually for world-wide distribution and use was felt to be of inestimable benefit to scholarly exchange. Another key issue was the use of the digital form as a means of preservation: with a fragile and rapidly deteriorating original, the digital version, if an adequate substitute for the original for most scholarly purposes, can allow access to the actual physical object to be restricted. With some materials, the object may not survive for much longer, and the digitised image may be all that we are left with. While not a perfect situation, this is preferable to total loss of our intellectual history. Of course, this throws up new problems of preservation: how, in a rapidly changing world of technology, are we to preserve the digital forms themselves?

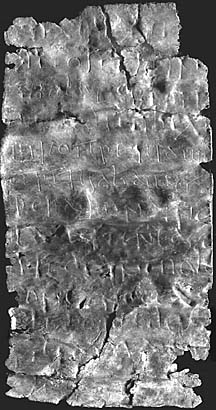

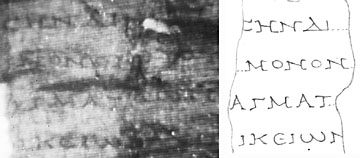

Section of a carbonised papyrus roll from Herculaneum now in the Bodleian Library (Ms. Gr. class. b. 1(l) 2) viewed on the left under a Video Spectral Comparator and right as transcribed at the time of its discovery. Dr. Dirk Obbink is leading a project to recover and transcribe the texts in the Bodleian as part of the international Philodemus project.

The workshop was an exciting meeting of groups of scholars interacting

across discipline boundaries and discussing new opportunities offered by

new technologies. The papers and discussions are to be published shortly

in the Office for Humanities Communication Publication Series and the volume

will be advertised in this newsletter.

This page was created on 19 October 1996