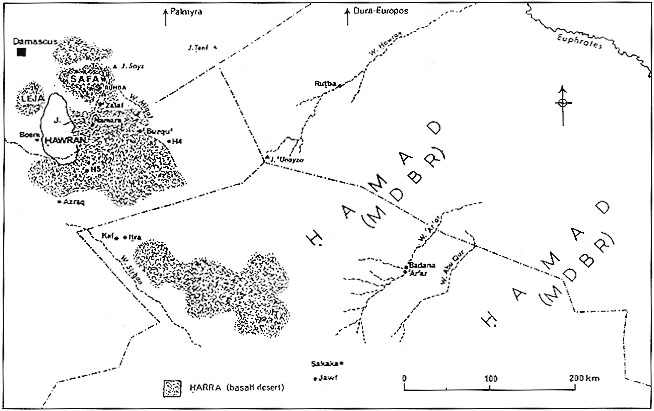

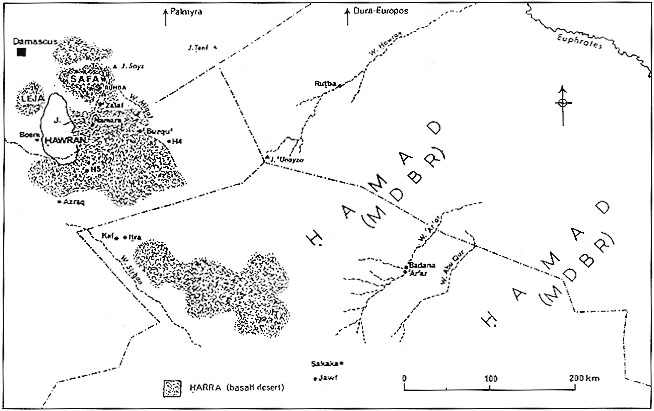

Sketch map of the area from which the Safaitic inscriptions derive

Kilroy in the DesertA Database of Bedouin Graffiti |

Literacy has never been of much use to nomads. Most have preferred to develop their phenomenal memories rather than trust the data they want to record or communicate to materials which are difficult to obtain in the desert and all too easily lost or damaged in tent-life.

For this reason, most nomadic societies have remained resolutely non-literate, functioning perfectly well at all levels without use of the written word. It is important to emphasise that this is a choice, since nomads, at least in the Near East, have been in contact with literate societies on the desert's edge for millennia and learning to read and write poses few problems to an individual with a well-developed memory.

However, between the first century BC and the fourth century AD the nomads on the borders of the Roman Provinces of Syria and Arabia learnt to write and practised the art with an extraordinary exuberance, leaving scores of thousands of graffiti on the rocks of the desert in what is now southern Syria, north-eastern Jordan and northern Saudi Arabia.

Sketch map of the area from which the Safaitic inscriptions derive

They spoke a language related to Arabic, which would have been incomprehensible to most of the peoples of the settled lands-who spoke Aramaic and Greek. The script they wrote in (which was labelled "Safaitic" in the 19th century) was a form of the South Semitic alphabet. Forms of this script were in use throughout western Arabia and in Ethiopia, but would have been entirely foreign to the inhabitants of the Roman Provinces of Syria and Arabia. Moreover, although this script is related to other forms of the South Semitic alphabet it is sufficiently distinct that someone familiar with one of the other forms would have had difficulty reading it.

Thus, whatever their reasons for learning to read and write, it is unlikely that communication with the outside world was one of them. Nor does communication within their own society seem to have been uppermost in the minds of those who embraced literacy. After all, there would have been a distinct shortage of soft or portable materials on which to write-the price of papyrus or parchment put them beyond the reach of most people, and pottery was not readily available in the desert, so, unlike people in the settled areas, the nomads could not use sherds to write on.

We do not know how or why they learnt to write but we might speculate that a nomad, perhaps guarding a caravan, may have seen a merchant from Arabia writing a letter and said "teach me to do that". Having learnt this skill, he would have showed it off to his friends and relatives. Indeed, we have found several examples of the Safaitic alphabet written on rocks, but in each case in a different order: the letters being grouped according to the individual writer's perception of similarities between different letter-shapes-an obvious mnemonic tool. None of these orders bears any relation to the traditional alphabetic orders of the North-West or South Semitic alphabets and this suggests that the art of writing spread informally from one individual to another and was not taught in schools, where rote learning of a fixed alphabetic order is the norm.

Given that the only writing materials readily available in the desert were rocks, and flints with which to scratch them, literacy cannot have seemed of much practical use to these nomads, and they might well have ignored it. Instead, however, they used it to while away the time during the long hours spent guarding the grazing flocks and herds or keeping watch. Over 20,000 of these "inscriptions" have been found so far and these are merely the results of a handful of expeditions over the last 140 years. Wherever one goes in the lava desert east of the Hawran, one comes across literally thousands of these texts. They were written by men and, to a lesser extent, by women and by slaves. Given that the desert could not have supported a huge population at any one time, the vast numbers of texts (which can probably be reckoned in hundreds of thousands) suggest the existence of almost universal literacy among these nomads. One is thus faced with the curious paradox of near-universal literacy in a society which had no practical use for it and which therefore remained, to all intents and purposes, "non-literate", its population using the skill purely as a pastime; while, by contrast, in the settled, literate, societies of Roman Syria and Arabia, it is very doubtful if more than a minority of individuals could read and write.

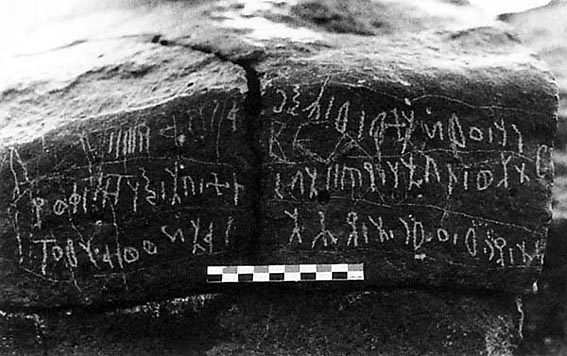

Safaitic text from the Wadi Sham inscribed boustrophedon (CRAI 1996,

461 no. E2)

The Safaitic inscriptions are almost entirely works of self-expression rather than of communication-graffiti rather than messages. The only texts which might be said to serve a useful purpose are those used as grave-markers, which were placed on the large cairns built over the graves of certain individuals. But these texts are rare and are expressed in exactly the same terms as the graffiti, i.e. "by so-and-so son of so-and-so, etc." with the addition that "the cairn is his/hers".

Though always laconic and often enigmatic individually, these thousands of graffiti when taken together provide a rich source of information on the way-of-life, religion, social structures and history of the nomads of the Syro-Arabian desert in the Roman period and of their relations with the authorities and the populations of the settled regions. They also tell us much about their personal lives, their hopes and griefs and relationships, for these are entirely personal documents. Thanks to the Safaitic graffiti we know far more about the daily lives of these nomads than we do about any other sector of the population in these provinces.

They are therefore of much greater importance than at first they might appear. They are potentially of as much value to historians of the Roman East as they are to linguists. Unfortunately, the state of publication of most of the texts is inadequate, often inaccessible and frequently misleading, and research tools such as a dictionary and an up-to-date list of names are non-existent. The texts are therefore very difficult for the non-specialist to use.

The Safaitic Database Project was established to enter the texts of all the known Safaitic inscriptions onto a computer database, together with translations and all available information about them, including a full apparatus criticus. The intention is to use this database to produce up-to-date editions (and re-editions) of the texts and to provide the "raw material" for vocabularies, onomastic indexes and studies, concordances of the, often lengthy, genealogies in the inscriptions, and so on; and thus to make the information in the inscriptions more easily available.

At the same time, the Safaitic Epigraphic Survey Programme is working in Syria to rediscover, and make a photographic record of, the inscriptions copied in the 19th and early 20th centuries, often by people who could not read the script, so that the readings can be verified. In the process, several thousand previously unknown texts have been discovered, recorded and entered on the Database.

The Safaitic Database Project is based at the Oriental Institute, Oxford and has been in receipt of a three-year Leverhulme Research Fellowship (1995-1997) as well as major grants from the University, the British Academy, the British Institute at Amman for Archaeology and History and the Seven Pillars of Wisdom Fund. It is a joint project of the Faculty of Oriental Studies, Oxford and URA 1062 du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Paris.

The Safaitic Epigraphic Survey Programme is a joint project of the Faculty of Oriental Studies, Oxford, and the Directorate General of Antiquities and Museums of Syria and is funded by the British Academy, the British Institute at Amman for Archaeology and History, the Seven Pillars of Wisdom Fund and URA 1062 du CNRS, Paris. Work on both projects is continuing and it is hoped that the first publications will be ready for the press by the end of 1998.

M.C.A. Macdonald. (michael.macdonald@orinst.ox.ac.uk)

| Created on |