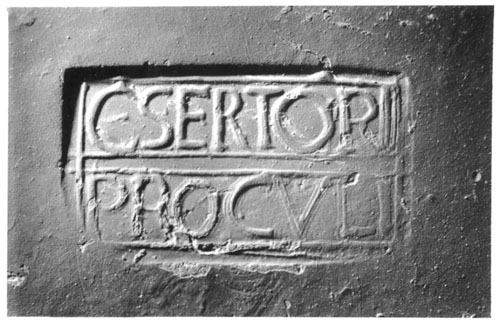

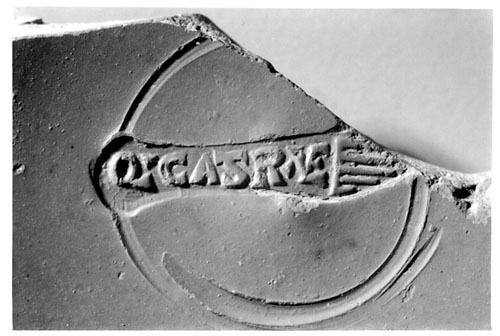

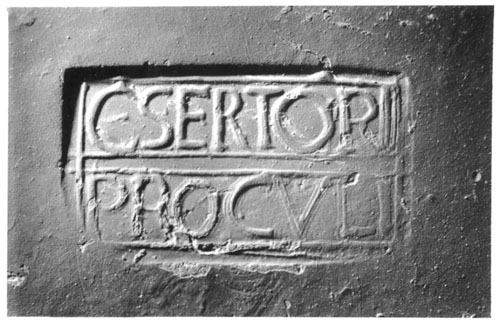

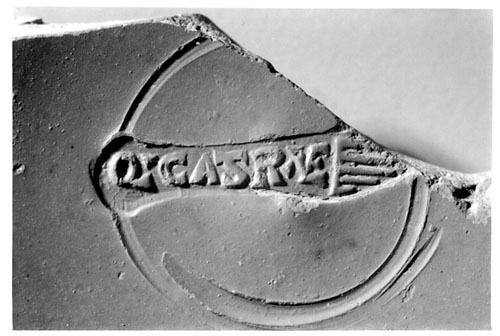

Typical potters' stamps on Italian sigillata: signatures of C. Sertorius Proculus (above) and Q. Castr(icius) Ve( ) (below).

|

CSAD Newsletter 9, Winter 2002 |

The opinion quoted above was expressed by Professor Moses Finley in his 1973 publication, The Ancient Economy. He was perhaps rightly critical of some of the more exaggerated claims made on behalf of the makers of fine ceramic tableware in Italy in the first century AD. Yet Italian terra sigillata (a modern but more neutral term than the traditional 'Arretine Ware') did find its way to every part of the Roman Empire. It contributes to the epigraphic record in the sense that makers' names were regularly impressed into the vessels before firing; and whilst these inscriptions are often highly abbreviated, they are prolific and they enable us to trace the evolution of the industry in greater detail than is possible for any other artefact of the Roman period.

Modern research has shown that this ware evolved from the preceding tradition of black-slipped wares in Etruria and the Po Valley during the third quarter of the first century BC. From about 25 BC onwards it began to be exported, at first to supply the army in Gaul and the Rhineland, and by the death of Augustus in AD 14 it was known throughout the Empire, from Spain and Morocco to Egypt and the Middle East. Pieces have even been found as far afield as the east coast of India. The name-stamps first attracted attention as worthy of study as long ago as 1492. In this year a considerable quantity of pottery was recovered at Arezzo from the bank of the River Castro near the Ponte delle Carciarelle, and the stamps were carefully recorded by Marco Attilio Alessi, who was about 22 years old at the time. His drawings have come down to us through two manuscripts, preserved at Florence and Arezzo respectively. However, in recent years the basis for all discussions of the stamps and of the relative importance of different workshops has been the Corpus Vasorum Arretinorum, compiled by August Oxé between 1896 and 1943 and eventually edited for publication in 1968 by Howard Comfort.

Oxé's catalogue comprised some 18,000 entries and it is about to be replaced by a Second Edition, prepared in Oxford by the writer during the last seven years. The new edition contains roughly twice as many entries, gathered under some 2,500 names, and these are often accompanied by far more information with regard to the findspots of the vessels, their shapes and their dates. It will provide the opportunity for a substantial reassessment of Finley's ungenerous opinion, and will reveal the functioning of an industry which could be highly sophisticated and in which some players were far more than "modest men."

We now know substantially more than Oxé about the sources of the ware, for in addition to Arezzo and Pozzuoli, the only production centres which could be identified for certain in his day, we now know of substantial workshops at Pisa, at sites in the Val di Chiana and along the Tiber Valley, and at Lyon in Gaul. The greatest body of early research was also in Gaul and Germany, where the Italian ware was driven off the market in the Tiberian period by distinctive Gaulish products (the so-called "samian" ware). In the Mediterranean region, however, Italian Sigillata continued to be exported for at least another century: this has become increasingly apparent with the growth in the publication of Roman pottery from Mediterranean sites.

At the height of its success, there were some very big producers of Italian Sigillata, and it is in respect of these that we can begin to ask how the ware was distributed. It is an abiding puzzle that an inland site such as Arezzo should have been capable of generating exports that travelled throughout the Roman World. Indeed, the greatest enterprise in Italian Sigillata, that associated with the name of Cn. Ateius, surely owed its success at least in part to having moved from Arezzo to Pisa on the coast, greatly reducing the cost of long-distance exports. The products of Ateius are most prolific in the western Mediterranean and the scarcity of finds from Arezzo itself long raised doubts as to whether he worked there at all. The discovery of production waste bearing his name there in 1954-55 finally resolved this uncertainty, and this was followed ten years later by the discovery of the major production site at Pisa, at which he and/or his freedmen were the dominant producers. There is now good reason to infer an actual migration from the one site to the other in about 5 BC. The subsequent history of this enormous enterprise (responsible for some 16 per cent of the total number of stamps in the catalogue) seems further to justify the inference that Ateius moved his operation to Pisa specifically in order to benefit from access to the sea and from the potential of maritime exports. This was indeed an enterprise of the broadest vision and here surely we have quite a substantial 'Wedgwood'.

For some of the major producers at Arezzo itself we now have a large enough body of data to look at their individual patterns of distribution, and here some suggestive differences emerge which seem to imply the presence of market forces which are not simply geographical. P. Cornelius is firmly located at Cincelli 8 km. from Arezzo, whilst L. Gellius is also somewhere nearby, though perhaps not in Arezzo itself, where vessels signed by him are scarce. They are broadly contemporary, Gellius having been active c. 15 BC-AD 50 and Cornelius for a slightly shorter period within the same over-all span. Their patterns of distribution, however, are markedly different. Whilst in Italy their representation is broadly comparable, Cornelius has a substantial western export market in the Iberian peninsula and Morocco where Gellius is sparsely attested. Gellius, on the other hand, enjoys a major penetration of northern Italy and right along the Danube, where Cornelius is hardly represented at all. Why should this be? Clearly, these workshops were not just putting their wares up for sale to whoever passed by their front door. Was the Gellius workshop perhaps to the north of Arezzo, with better communications across the Apennines to the Po Valley? Did the Cornelii own estates in Spain with consequent shipping interests which favoured the export of pottery in that direction? Such patterns seem more likely to reflect a deliberate exploitation of certain markets by the producers (with concomitant links between production and distribution) than a selection of products by the consumers: this is typical of the kind of challenge to our understanding of marketing structures and trade which this material now presents.

As the number of known centres of production has increased, the question has repeatedly arisen whether the same names occurring on different production sites are coincidental or reflect some genuine relationship between them. In the case of minor potters, the coincidence of the names may be no more than that or it may represent a migration by one individual from one site to another: this is a phenomenon which is now well attested amongst the later Gaulish centres. But what about the larger concerns? There are stamps reading Atei or Cn. Atei which originate from Lyon and indeed from La Graufesenque in the Aveyron. Rasinius worked at Arezzo and possibly also somewhere on the Bay of Naples, but we have signatures bearing his name alone and in combination with Acastus and Rufus at Lyon. Signatures of C. Sentius, generally very similar in character, are known from both Etruria, northern Italy, Lyon, La Graufesenque and Asia Minor! How is this evidence to be interpreted? There is a natural inclination to argue back from the experience of modern times and to infer that Arretine entrepreneurs were maximizing their commercial potential by establishing subsidiary production closer to distant markets. However, the evidence rarely supports such a far-reaching conclusion.

Looking at the entire range of nomenclature on the Italian sigillata stamps, it is quite clear that there is no uniformity or rigour of style. A freedman might sign with his full tria nomina, or he might omit the cognomen, or he might on occasion use his cognomen alone. It is thus entirely possible that the signatures which appear to indicate distant subsidiaries of the larger workshops actually represent former slaves who have been manumitted and who have migrated elsewhere to set up on their own. In a distant market, such an individual might not need to use his cognomen in order to assert his identity. Stamps originating from Lyon and bearing the name of Cn. Ateius need not therefore imply any control by or continuing connection with the 'parent' workshop.

Typical potters' stamps on Italian sigillata: signatures of C. Sertorius Proculus (above) and Q. Castr(icius) Ve( ) (below).

On the other hand, there are also a few stamps which show well-known potters in partnership, apparently working at some distance from their original place of work. The most notable of these is the combination Xanthus + Zoilus. These are two prolific members of the 'Ateius group' working at Pisa, and yet their names appear coupled together only on products made at Lyon. In this instance the only plausible explanation seems to be some kind of deliberate attempt by existing workshops to enhance their market share by setting up outlying production facilities in mutual collaboration. The core of the new catalogue will be published in electronic form on a CD, which will enable users to pursue all kinds of queries and to investigate many different patterns in the data. Finley criticised earlier research on this material as a "great edifice" built on foundations which were inadequate to support it. Now a foundation with far greater potential has been laid: I have hinted at the kinds of enquiry that it suggests, and it will be exciting to see where it leads us over the coming years.

Philip Kenrick

Institute of Archaeology, 36 Beaumont Street, Oxford, OX1 2PG

e-mail: philip.kenrick@archaeology.ox.ac.uk

Home | What's New | Events | Images | Links

| Created on |