A Corpus of Writing-Tablets from Roman Britain

(A British Academy Research Project)

Project Directors - Dr. A.K. Bowman FBA, Prof. J.M. Brady FRS FEng., Dr. R.S.O. Tomlin FSA, Prof. J.D. Thomas FBA

Research Assistant - Dr J. Pearce

|

A Corpus of Writing-Tablets from Roman Britain(A British Academy Research Project)Project Directors - Dr. A.K. Bowman FBA, Prof. J.M. Brady FRS FEng., Dr. R.S.O. Tomlin FSA, Prof. J.D. Thomas FBA Research Assistant - Dr J. Pearce |

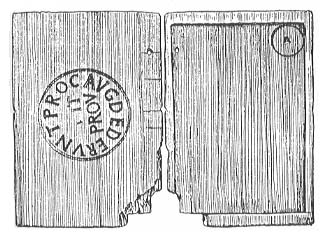

Lead 'curse tablets' comprise thin rectangular sheets which, when complete and unrolled, generally measure 6 - 12cm long and 4 - 8cm wide, although many survive only as fragments. Though often described as 'lead', metallurgical analysis of tablets from Bath, for example, shows that many are better characterised as pewter, given their high tin content. The sheets, having been cast and / or flattened, were generally trimmed to provide a roughly rectangular surface area. The text was inscribed on the tablet with a point, perhaps a stylus like those used to write on wax tablets, and the tablet was then rolled or folded with the written surface innermost, and the ends folded over. This is the state in which they are usually found. The tablets were sometimes pierced by nails, which occasionally survive in situ, although more frequently only the holes indicate their original presence. This nailing provides one explanation of the name of defixio by which these artefacts are often known (the Latin verb from which it is taken, defigere, has the meaning both to fasten and to curse). Some tablets may have been nailed to a wall or post prior to deposition, perhaps to display their message. However nails often seem to have been hammered through the blank side, making the text invisible if the tablet had been on view (Click here for images of curse tablets).

In Britain the majority of lead tablets seem to have been deposited on temple sites, famously at Bath and at Uley in Gloucestershire. At Bath they were deposited in the hot spring. Instances are also recorded from other 'watery' contexts, graves and settlements. On settlements occasional evidence suggests a preference for wet places; for example individual tablets come from the ditch of a fort and the drain of a bathhouse. As tablets are often found outside formal excavation, it can be difficult to identify the type of site on or context in which they were deposited. This is therefore a question for which we need much more reliable information.

In order to read the texts the tablets must be carefully unfolded. Given their usually brittle condition, this process can only be successfully performed in the laboratory. Distortion and cracking from folding and rolling have frequently affected the appearance of the texts. When freshly cut the strokes of the text would have shone against their background, but subsequent oxidisation has made both tablet surface and incisions the same dull grey. Corrosion has sometimes removed or damaged the surface of the tablets. Light must be cast from several different angles on to the tablet in order to render visible all the separate strokes that make up letters. The results of this examination are produced in drawings, on which the readings and subsequent translations of the tablets are based. It is impossible for a single photograph to reproduce adequately all the parts of all letters.

Most texts were written in the cursive script like that on wooden writing tablets from Vindolanda, although capitals were occasionally used. While the text may be set out in what to modern readers is a conventional order, many other formats have been recorded. Letters or words may be written backwards, word order may be reversed, and lines may be written in alternating directions, from left to right and then right to left (known as boustrophedon, the Greek term for the movement of the plough across a field). While most texts from Roman Britain are in Latin, occasional texts may be in a Celtic language. Some tablets were marked with only a series of scratches, or were not even marked at all. The very act of marking, folding, nailing and depositing a tablet must therefore have been as effective for some as the written appeal.

Typically texts from Bath and Uley relate to theft, at Bath for example of small amounts of money or clothing from the bath-house, at Uley of animals or farm implements. In formulaic, often legalistic, language tablets appeal to a deity, for example Sulis at Bath or Mercury at Uley, to punish the known or unknown perpetrators of the crime until reparation is made. The deity is typically requested to impair the physical and mental well being of the perpetrator, by the denial of sleep, by causing normal bodily functions to cease, or even by death. These afflictions are to cease only when the property is returned to the owner or disposed of as the owner wishes, often by its being dedicated to the deity. A prayer to Neptune and possibly another water deity, Niskus, found on the foreshore of the Hamble Estuary, Hampshire, by a metal detectorist, concerning the theft of a gold coin (solidus) and some silver coins (argentioli) illustrates some of the typical elements.

domine Neptune, / tibi dono hominem qui / (solidum) involavit Mu- / coni et argentiolos / sex. ideo dono nomina / qui decepit, si mascel si / femina, si puuer si puue- / lla. ideo dono tibi, Niske, / et Neptuno vitam, vali- / tudinem, sanguem eius / qui conscius fueris eius / deceptionis. animus / qui hoc involavit et / qui conscius fuerit ut / eum decipias. furem / qui hoc involavit sanguem / eiius consumas et de- / cipias, domine Nep- / tune.

Lord Neptune, I give you the man who has stolen the solidus and six argentioli of Muconius. So I give the names who took them away, whether male or female, whether boy or girl. So I give you, Niskus, and to Neptune the life, health, blood of him who has been privy to that taking-away. The mind which stole this and which has been privy to it, may you take it away. The thief who stole this, may you consume his blood and take it away, Lord Neptune

Note. The solidus is a gold coin, the argentiolus a silver coin. Niskus is possibly another water deity comparable to Neptune.

(Click here for a photograph and drawing of the tablet of which this is the translation. The tablet was published by Dr Roger Tomlin in Britannia 28, 1997, pp. 455-458.). The text and translation are the copyright of Dr Tomlin and are reproduced here with his permission.

Some inferences can be made concerning the authors of the tablets. The texts are sometimes concerned with the recovery of small sums of money or everyday items, suggesting that to purchase and dedicate tablets may not have been too expensive. The name forms on the tablets suggest that both dedicators and wrongdoers were often not of citizen status, although these name forms are also affected by the date of the tablet. This evidence suggests that the texts give an insight into the world of the lowlier but far more numerous group than the small proportion of Romano-Britons able to commission inscriptions on stone. Competence in writing and in Latin shows a high degree of variability. Groups of tablets from elsewhere in the Roman world seem to have been produced by the same individual or closely associated group who may have acted as professional scribes, but no two same hands were identified at Bath for example. While it is unlikely that everyone who commissioned tablets at Bath would have been capable of writing them, this variety of hands suggests that many people did not need the services of a professional scribe. A larger proportion of the population may have been literate in at least some parts of Roman Britain than has been previously thought.

Whilst the British curse tablets draw on a common Greco-Roman tradition, they show some particularities in comparison to similar texts from other provinces. Appeals for the punishment of theft account for the vast majority of British texts, but elsewhere writers of tablets also aimed to influence the course of love affairs, to sway the outcome of trials in the law courts and to 'fix' races in the circus. In other provinces tablets have also been found in contexts from which they are rare or unknown in Britain. In the eastern Mediterranean and North Africa for example tablets were more often deposited in graves. They could be 'posted' to the dead via the lead or ceramic tubes that were intended for the pouring of libations during family gatherings at the tombs of their ancestors. The messages passed through this 'infernal postal system' appealed to the spirit of the deceased, usually of an individual who had died young, to act on the dedicator's behalf. In North African cities curse tablets directed against charioteers were deposited either in cemeteries near circuses or even within circuses, especially at the starting gates and turning posts. The historian Tacitus records evidence of magical practices surrounding the death of Germanicus, step grandson of the emperor Augustus, in AD 19. Lead tablets bearing his name were found with charred human bones and ashes in the floor and walls of the room in which he died. Similar motives may explain the occasional curse tablets recorded on settlement sites from Britain, although we usually lack information on their precise context.

It is not only therefore the subject matter of the texts that allows valuable insights into Romano-British society. Knowing the context from which they come is also important. At the very least it allows us to assess the periods, areas and site types on which tablets were used. Distribution patterns allow us to assess the spread of familiarity with Latin and of Roman religious rituals or magical practices in Britain. When groups of tablets can be put together then more detailed assessments are possible of language, literacy and religious practice. Lead tablets therefore provide a fascinating range of information on many subjects, religious belief and practice, the degree of literacy in Latin in Britain, bath-house culture at Bath and the more rural world of Uley. Most documents from the ancient world were largely written by and for elites and reflect their pre-occupations. In these tablets however we hear the voices of more ordinary provincial Romans.

While the planned corpus will include only writing tablets, we also welcome information on other types of 'documents' that are currently being found with metal detectors. Military diplomas are texts incised on bronze issued to auxiliary soldiers on their discharge from the army to record their acquisition of Roman citizenship. Individual copper alloy letters from monumental inscriptions are sometimes found which have become detached from their stone setting. Metal artefacts often bear writing of some sort, whether cast, incised or punched. Maker's stamps and graffiti on vessels, weapons, jewellery, tools and equipment provide evidence of the organisation of production, military supply, commerce and property ownership. Inscriptions on votive plaques or tablets, sometimes in precious metals, may record their dedication to a deity and the name of the donor. Other items, including relatively everyday artefacts, may also register their donation to a deity, while some bear a motto or a record of their being given as a gift. Small rectangular lead labels were attached by cord to either bundles of documents or batches of goods in transit, while lead tags sometimes sealed the ends of such cords. These tags can indicate the goods supplied or those who sent or received them. Metal ingots and lead weights bearing stamps and inscriptions are also not infrequent finds. These sorts of items from Roman Britain are catalogued with descriptions in RIB II.

We would therefore be very pleased to hear of new discoveries of curse tablets and other Roman period metal artefacts bearing writing. Contact details including the postal and email addresses of the project are given in the introduction. The CSAD website also includes information on some of theother projects undertaken by the Centre relating to ancient documents and has links to many websites related to the study of the classical world.

(Copies of this document were distributed through the Portable Antiquities Scheme, July 2000)

CSAD | Introduction | Letter to museums | Description of curse tablets | Progress report | Images and references